Predicting Utility Site Disruptions

Anticipating Utility Site Disruptions

Our business question in this situation is that a Utility company wants to predict their site disruptions in order to minimize the amount of time that their service is down. My boss has come to me and asked me to generate a report every morning in order to preemptively predict these disruptions so that she can send out service technicians to their first location in the morning.

Each service station has a fault severity of 0 (no issues), 1 (minor issues), or 2 (major issue). The other data that are given to us are fairly abstract in nature, but we know each observation is a single instance of a service check on the station.

#import libraries

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

from functools import reduce

from sklearn.ensemble import GradientBoostingClassifier, RandomForestClassifier

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score, precision_score, f1_score, recall_score

After importing the libraries, we read in the data, which is given to us in 4 different tables. After taking a look at each one, we clean them up enough to combine together

df_list = [event_tb, log_tb, resource_tb, severity_tb, train_tb]

for item in df_list:

print(item.head())

id event_type

0 6597 event_type 11

1 8011 event_type 15

2 2597 event_type 15

3 5022 event_type 15

4 5022 event_type 11

id log_feature volume

0 6597 feature 68 6

1 8011 feature 68 7

2 2597 feature 68 1

3 5022 feature 172 2

4 5022 feature 56 1

id resource_type

0 6597 resource_type 8

1 8011 resource_type 8

2 2597 resource_type 8

3 5022 resource_type 8

4 6852 resource_type 8

id severity_type

0 6597 severity_type 2

1 8011 severity_type 2

2 2597 severity_type 2

3 5022 severity_type 1

4 6852 severity_type 1

id location fault_severity

0 14121 location 118 1

1 9320 location 91 0

2 14394 location 152 1

3 8218 location 931 1

4 14804 location 120 0

#Merge the dataframes together

df = reduce((lambda df1, df2: pd.merge(df1, df2, on='id')), df_list)

df.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

Int64Index: 61839 entries, 0 to 61838

Data columns (total 8 columns):

id 61839 non-null int64

event_type 61839 non-null int32

log_feature 61839 non-null int32

volume 61839 non-null int64

resource_type 61839 non-null int32

severity_type 61839 non-null int32

location 61839 non-null int32

fault_severity 61839 non-null int64

dtypes: int32(5), int64(3)

memory usage: 3.1 MB

After taking a look at each variable using value counts, we see that each feature is fairly abstract, it difficult to see at face value what each feature physically corresponds to. This will mean that we will not be able to semantically group any features together.

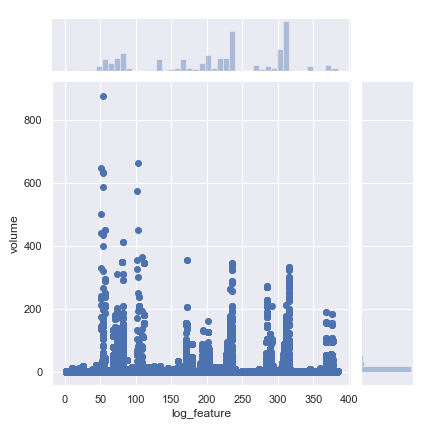

Since log_feature and volume came in the same file, we’ll look at how they relate to one another:

Taking the log of volume gives us a better scale, so we will be using the log transform of the ‘volume’ feature.

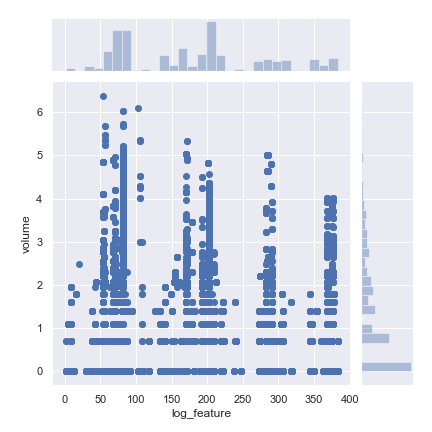

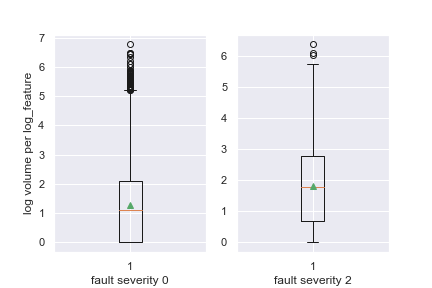

Let’s continue to look into the relationships surrounding log_feature by looking at a boxplot of how the volumes vary depending on our target: fault severity.

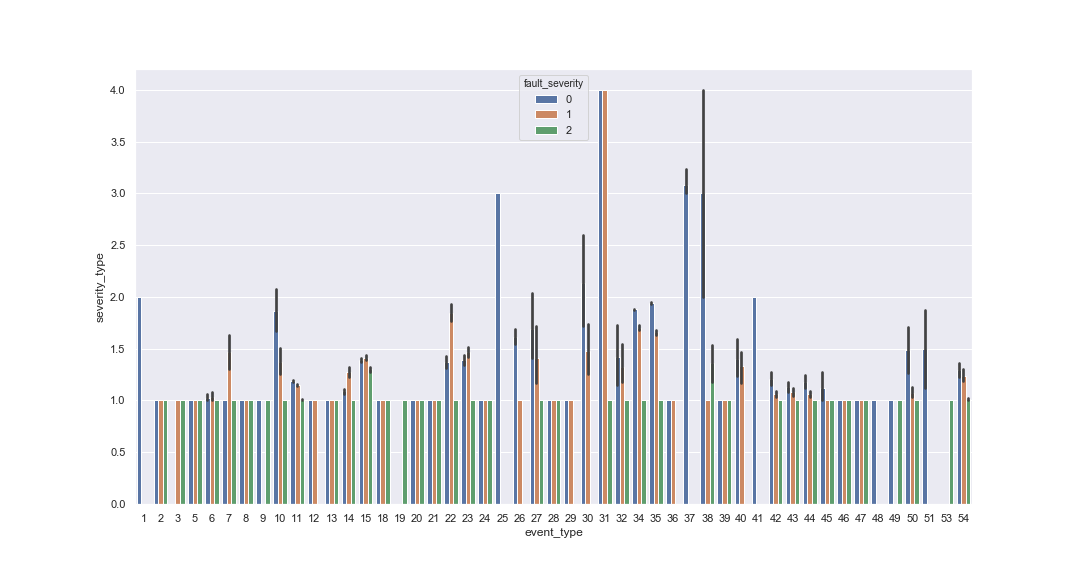

Lets take a look at some more graphs to try and get a sense of how the variables are related to one another.

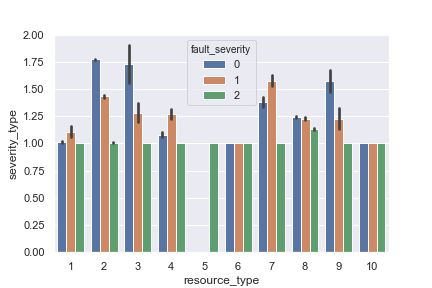

This graph shows the frequency of fault severity per resource type and severity type.

We can see that resource type 5 only has 2, or ‘critical’ fault severity. We can also see that resource types 2, 3, and 9 have higher chance of 0 fault severity.

We can see some relationships within each event type or resource type, but no real overarching trends. This is why we have models to pick up on the more subtle relationships between variables.

Lets prepare our data for the model by getting dummies on our object columns. After that, we will group our data by ID number, since we want to look at the fault severity at each ID.

data = data.groupby('id', sort = False).sum()

First, we convert resource_type, severity_type, event_type, and log_feature to string values and use pd.getdummies on them, since we dont want our model to infer direction from different values (resource_type 2 is not higher than 1).

We then separate the feature and target variables, and randomly select training and test rows by using sklearn’s train_test_split. We then decide to use the gradient boosting classifier to predict to fit to our data and predict.

#The Gradient Boosting Classifier fits our data the best

gbc_model = gbc.fit(x_train, y_train)

gbc_accuracy = accuracy_score(y_train, gbc.predict(x_train))

print(gbc_accuracy)

#setting up prediction probabilities for each row

y_pred_proba = gbc.predict_proba(x_test)

y_pred = gbc.predict(x_test)

After predicting the probability, we want to create an output that is easily readable by our supervisor so that they can send the service techs to the correct locations.

#Make a DataFrame of the predictions

result = pd.DataFrame({

"id": x_test.index,

"Predicted fault_severity": y_pred,

"prediction_probability_0": y_pred_proba[:, 0],

"prediction_probability_1": y_pred_proba[:, 1],

"prediction_probability_2": y_pred_proba[:, 2]},

columns =['id', 'Predicted fault_severity', "prediction_probability_0",

"prediction_probability_1", "prediction_probability_2"])

result.head(10)

Next, we sort the values by most likely to have a severe fault.

result.sort_values(['prediction_probability_2'], ascending= False, inplace= True)

result.head(20)'

After we get this table, all we need to do is write it to a csv and send it to our boss so the service techs can do their thing!

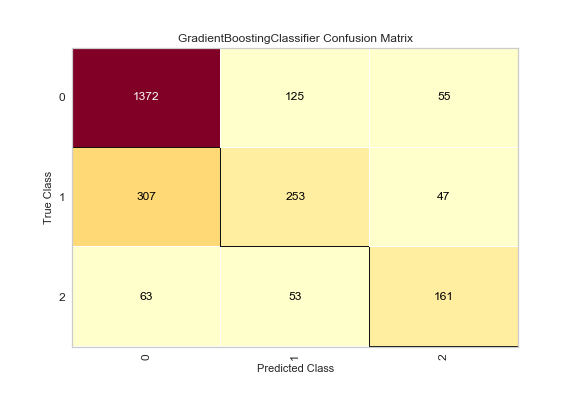

Our predictions with the basic model are decent, but as you can see in the confusion matrix below, there is only a 58% chance that we will predict a fault severity of 2 correctly.

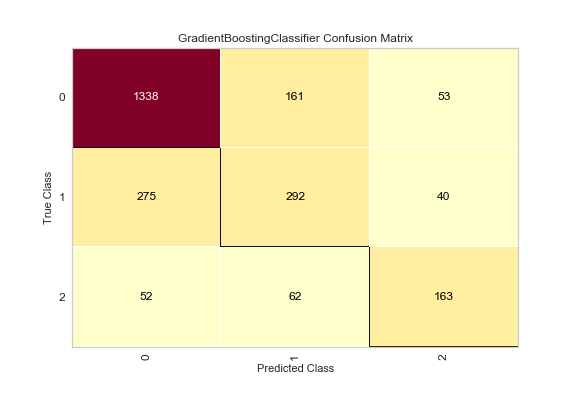

After some hyperparameter tuning, we can increase this to 63% chance that a 2 is predicted correctly, and nearly 80% chance there is at least a minor issue with the site. Given that the assignment is to give insight into a technician’s first assignment of the day, 63% is a considerable increase to chance for very low risk.

Basic GBC Model:

Parameter Tuned GBC:

Graphs made by using matplotlib, seaborn, and yellowbrick.

Link to Jupyter notebook may be coming soon here, or can be sent upon request.